In the year 2000, in the academic halls of the Collège de France in Paris, the world's most distinguished mathematicians convened to tackle a historic task. Organized by the non-profit Clay Mathematics Institute, the meeting aimed to identify the most significant unsolved problems in the field, a challenge they dubbed the

With a collective nod, they selected seven, each so profound and complex that a $1 million prize was pledged to the first person to solve any one of them. For a field often seen as abstract and detached, this was a moment of global attention, a public acknowledgment of the immense intellectual effort that goes into pushing the frontiers of human knowledge. So far, only one of these problems has been definitively solved. The man who did it, Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman, would become as famous for what he rejected as for what he achieved.

The problem in question was the Poincaré Conjecture, originally posed by French mathematician Henri Poincaré in 1904. At its core, it's a question about the nature of space itself. Poincaré suggested that if you have a three-dimensional space with no holes, it can be continuously reshaped into a sphere without needing to be ripped or cut. To put this in a more relatable context, think of a simple blob of clay—you can mold it into a perfect sphere. A topologist, someone who studies the properties of space that remain unchanged under deformation, would consider a pillow and a basketball to be the same, or "topologically equivalent," because one can be stretched and squashed into the other without creating a new hole or closing an existing one. In contrast, a donut and a coffee mug are also topologically equivalent because they both have a single hole, making them fundamentally different from a sphere.

Poincaré’s conjecture was a bold statement that any three-dimensional shape that has no holes is, in essence, a hidden sphere. He believed it to be true, but a century of brilliant minds could not find a way to prove it.

The problem’s difficulty was magnified when it was generalized to higher dimensions. Proving it for four dimensions was a monumental challenge on its own, finally solved decades later by other mathematicians. But the original, three-dimensional case, Poincaré's own conjecture, remained a persistent and tantalizing riddle.

The Man Behind the Proof

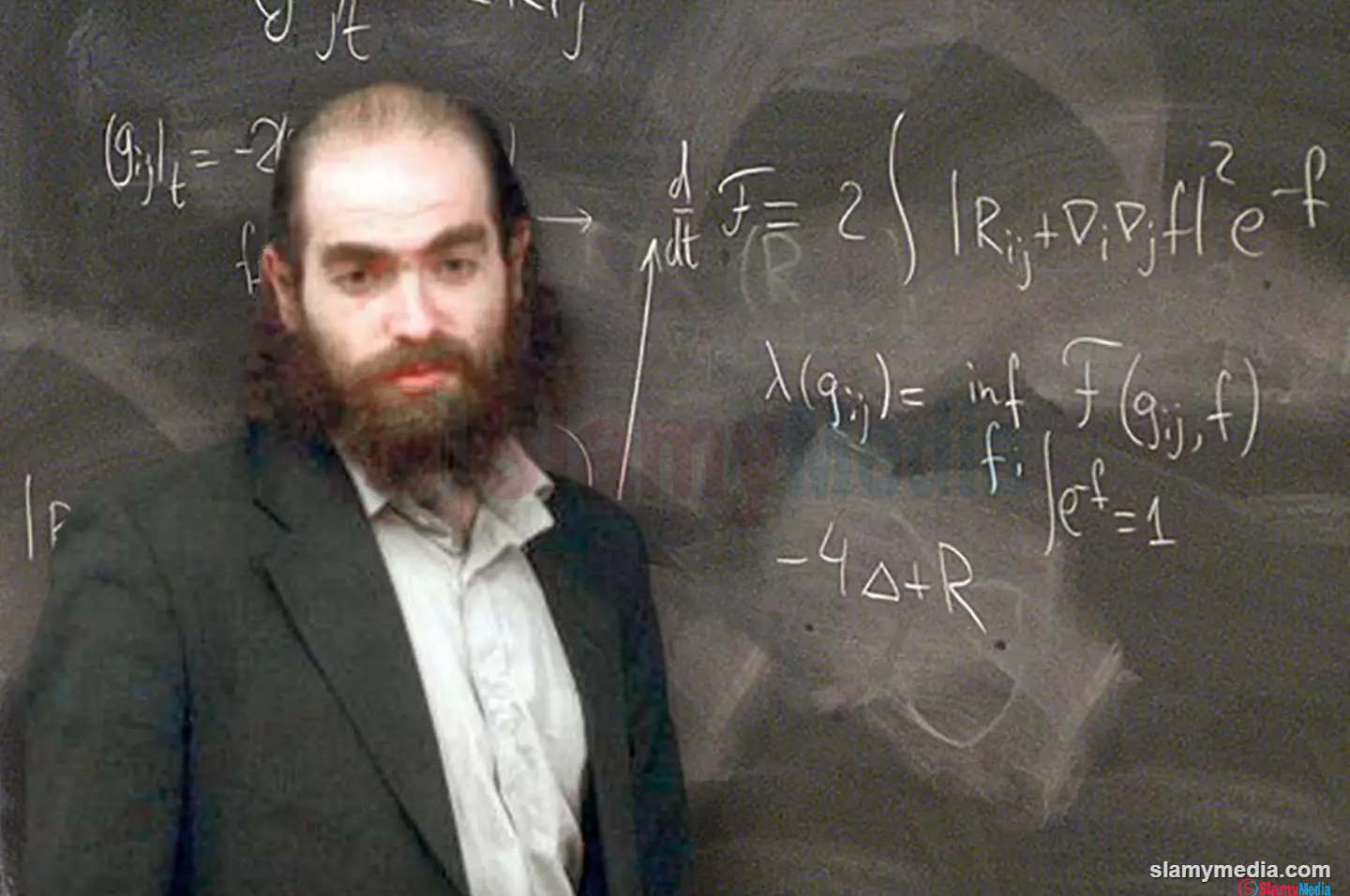

In 2002, a mysterious paper appeared on arXiv.org, a public forum operated by Cornell University. Titled "The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications," the paper contained a dense, complex, and elegant solution to the Poincaré Conjecture. The author was a largely unknown Russian mathematician named Grigori "Grisha" Perelman.

Perelman's journey began in the Soviet Union, in Saint Petersburg, where he attended an elite high school specializing in mathematics. His teachers immediately recognized his exceptional intellect, noting his unwavering focus. As his teacher, Valery Ryzhik, told author Masha Gessen in her book on Perelman, Perfect Rigor, Grisha seemed so "tuned to the learning process" that he could not be distracted. This intense discipline paid off when, at 16, he won a gold medal with a perfect score at the International Mathematical Olympiad. This victory was a golden ticket, granting him admission to Leningrad State University without having to take the entrance exams, a crucial bypass of the university's discriminatory quota system that limited the number of Jewish students.

His academic path continued to be one of quiet, singular focus. After graduating, he was accepted into the renowned Steklov Mathematical Institute’s St. Petersburg branch, an almost unheard-of accomplishment for a Jew. Influential figures, including the respected mathematician Alexander Alexandrov, campaigned on his behalf, offering to personally supervise his graduate work.

With the loosening of the Iron Curtain in the late 1980s, Perelman was given a rare opportunity to travel abroad. Prominent mathematician Mikhail Gromov arranged for him to give talks in the U.S. on geometry, his area of expertise. This led to post-doctoral fellowships at NYU and Stony Brook University. During his time in the U.S., his passion for math was only matched by his quirky habits, like walking from Manhattan all the way to South Brooklyn just to get his favorite black bread from a Russian shop.

After a prestigious fellowship at UC Berkeley, American universities vied to recruit him. When he gave a guest lecture at Princeton, the university’s top brass was so impressed they offered him an assistant professorship and asked for his CV. Perelman’s now-famous response was: "...why would you need any more information?" He reportedly refused the job because he wanted nothing less than a tenured position, while Princeton wanted the 29-year-old to earn his way up.

When Tel Aviv University offered him a full professorship, he rejected that too, stating he could work better back in his homeland. He returned to the Steklov Institute in Russia, where he began to work in isolation on what no one knew was one of the most difficult math problems of all time.

The Path to the Solution

The key to Perelman’s proof lay not in a direct frontal assault on the Poincaré Conjecture, but in solving a much broader problem. In the late 1970s, American mathematician William Thurston proposed that any three-dimensional shape could be broken down into eight distinct geometric structures. One of these structures was the very 3D sphere at the heart of the Poincaré Conjecture. Thurston’s own theory, the Geometrization Conjecture, was even more ambitious than Poincaré’s, and he never managed to prove it.

But another American mathematician, Richard Hamilton, provided the critical blueprint. Hamilton developed a powerful mathematical tool called Ricci flow to study the evolution of shapes. Imagine Ricci flow as a process where heat spreads through an object, smoothing out any bumps or irregularities over time. Hamilton believed this tool could be used to solve both his and Thurston's conjectures, but he was stuck. He couldn’t figure out how to handle the "singularities," or "necks," that would form as the process progressed.

Perelman picked up where Hamilton left off. He introduced a groundbreaking process he called "surgery" to cut off these necks, allowing him to study the pieces of the shape separately. He realized that these pieces ultimately represented the simple shapes predicted by Thurston's conjecture. By systematically solving Thurston’s problem, he had, in turn, provided the proof for Poincaré’s.

After uploading his three papers—a total of 992 pages—to the internet, a move that bypassed the traditional peer-review process, Perelman emailed a handful of American mathematicians to give them a heads-up. This was completely out of character, as he had barely responded to colleagues for years.

For over three years, the mathematical community, intrigued and skeptical, scrutinized every line of his proof. But Richard Hamilton, the man whose foundational work Perelman had relied on, remained silent. Perelman was hurt by this apparent lack of interest, telling The New Yorker, “I had the impression he had read only the first part of my paper.” Author Masha Gessen offered an insightful explanation: Perelman had, in less than half of his first paper, moved past the point where Hamilton had been stuck for two decades. The silence was, perhaps, a testament to the emotional weight of seeing one's life's ambition "hijacked and then fulfilled by some upstart with unkempt hair and long fingernails."

By 2006, the consensus was clear: Perelman had solved the problem.

The Unconventional Choice

The world of mathematics prepared to honor its new hero. In a strange twist, two Chinese mathematicians, Cao Huai-Dong and Zhu Xi-Ping, claimed they had also proved the conjecture, but the mathematical community quickly dismissed their claim. The crown belonged to Grisha alone.

But he didn’t want it. In 2006, he was awarded the Fields Medal, the highest honor in math and widely considered the equivalent of a Nobel Prize. Perelman simply didn’t show up to the awards ceremony in Madrid. The president of the International Mathematical Union publicly expressed his regret, stating, "I regret that Dr. Perelman has declined to accept the medal."

His most famous act of defiance came with his refusal of the $1 million Millennium Prize. In a rare interview with a Russian newspaper, he explained his perspective: “I know how to control the universe. So tell me, why should I run for a million?” His disdain for self-promotion and fame was a defining characteristic. In another interview, he said, "I do not think anything that I say can be of the slightest public interest," and suggested that newspapers should "have more taste" in whom they choose to write about. He was once reached by a reporter on the phone and famously told them, “You are disturbing me. I am picking mushrooms.”

Despite offers to teach at institutions like MIT, Princeton, and Columbia, he turned them all down. Jim Simons, the renowned mathematician and investor who had elevated Stony Brook’s math department, reportedly offered Perelman any salary he desired. But Perelman refused and returned to the Steklov Institute in Russia, where he worked as a lead researcher for a salary of around $400 a month. Once, when he was paid a little extra from a grant, he insisted the money be returned to the Institute’s accounting office.

Grisha lived his life by his own, uncompromising set of principles.

Then, in December 2005, he quit his job. According to Masha Gessen, he told the Institute’s director, “I have nothing against the people here, but I have no friends, and anyway, I have been disappointed in mathematics and I want to try something else. I quit.” He withdrew from not just the mathematical world but from society as a whole. Very little is known about his life since, other than that he lives with his mother. Photos have circulated online of him appearing disheveled, a figure far removed from the accolades he chose to spurn.

The $1 million he refused was used by the Clay Institute to fund the "Poincaré Chair," a temporary position for young, promising mathematicians at the Henri Poincaré Institute in Paris.

Grigori Perelman's story is a modern-day fable, a thought-provoking testament to the immense power of human intellect and the deeply personal choices that define a life. It stands as a powerful reminder that for some, the pursuit of knowledge is a reward in itself, a personal quest that transcends the allure of money, fame, and societal validation. It’s a story not just about a mathematical solution, but about a man who, having solved one of the universe’s great mysteries, decided he had no need for its trivial prizes.

Reported by Tert Slamy.